Educator Tools

Ask yourself:

Ask yourself:

- Holocaust art is unique in its portrayal of time and place. How are the paintings and drawings created during the Holocaust different when compared to other eras and significant periods of history?

- How would you engage the subject of the Holocaust artistically? What key questions would you like to answer prior to creating an artistic response to the Holocaust?

- How does the architect Daniel Libeskind memorialize the Holocaust through his monuments and museums?

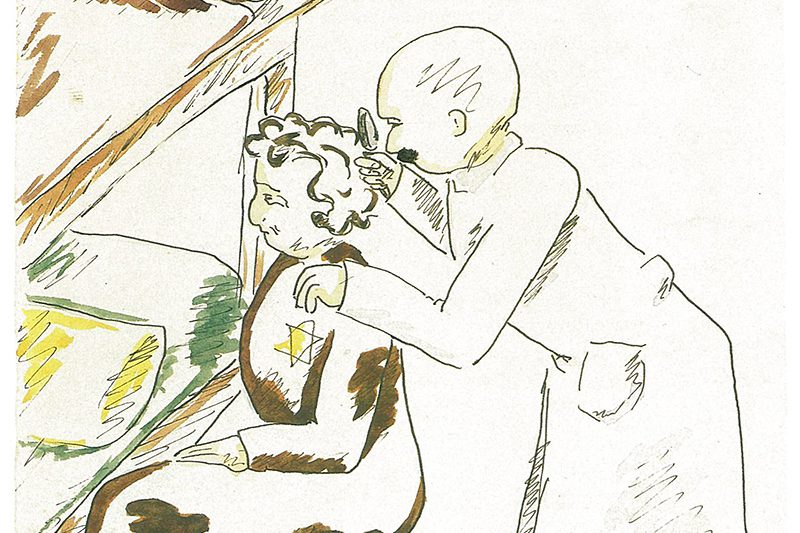

In this section, the Holocaust can be explored through a study of art and art history, examining how victims used artistic expression to communicate their protest, despair, and/or hope. By looking at what they reveal about life in the ghettos and camps, you can approach the works as historical artifacts.

You can examine the value of art by discovering and viewing the works of victims living in the camps, through artists commemorating the Holocaust through artistic creations, and through interpretations of the Holocaust as expressed in contemporary art by today’s students and teachers.

The Power of Holocaust Art

Art as an escape from reality

Art as reaction or resistance to the structural elements of society has performed multiple functions beyond documentation. The production of works of art reaffirmed and enabled artists to bridge the existential divide enforced through dominance connecting and reconnecting the individual artist to their past creativity. Art as creative act became an escape to another world repurposing long hours of idle tedium.

Art as a means of barter

Works of art also served a functional role in relationships as exchange or barter. Often, artists were commissioned to produce portraits from photographs by camp administrators. The exchange would occasionally provide the artist with more favourable food or even the opportunity to send messages.

Survivor Esther Lurie: “I managed to get hold of a pencil and some scraps of paper. I started to draw some of the various ‘types’ among the women prisoners. Young girls, who had ‘friends’ among the male inmates and who used to get gifts of food asked me to draw their portrait. The payment—a piece of bread.”

Art as a means of connection with the outside world

Art in its production and exchange played an important role for its creators offering distraction and connection while passing time and offering the possibility of small rewards. Many artists’ resistive acts were intended to reach the outside world and communicate camp conditions to the people “on the other side of the fence.” This dangerous act of resistance would often lead to dire consequences, as exemplified in the lives of Karel Fleischman and Leo Haas, inmates in the Nazi’s “model ghetto” Theresienstadt.

The artists’ quarters were searched in advance of a visit by the Red Cross during the summer of 1944, to prohibit the smuggling of paintings depicting the reality of the camp. The Germans sought to stem the flow of smuggled art and its shocking reality to the world outside Theresienstadt. Haas and Fleischman were interrogated and tortured, yet refused to communicate with their captors leading to their transfer to Auschwitz. Fleischman would die there. Both artists exhibited resolute determination and created art that challenged the public narratives of the Nazis while minimally sustaining the imprisoned artists through the abyss of isolation, exile, and isolation.

Consider the words of Dr. Karel Fleischman, an artist and doctor in Theresienstadt:

“I too have done all kinds of things. I helped others, thereby helping myself. I took up pencil and paintbrush and used them as a springboard to enter the world of the imagination. I wanted to see the world differently, experience it differently. In all the hundreds of paintings I have produced I always painted the same world, yet also a world that changes every second. A world beyond time.”

“I ignored reality. I read chronicles. I studied physics, chemistry, economics, languages and the history of art. I read books about geography and voyages to all places and at all times. I would close my eyes and still feel compelled to see everything. The doorbell rings—a threat. Crossing the road—torture. A note left on the table at lunchtime—trepidation. The door of my mother’s apartment—fear and worry. This is what life is like in the twilight.”

Subjects and style

The majority of works of art created during the Holocaust were stark, small, and spare. Most of these paintings and drawings were realistic and primarily made in the common media of watercolour, charcoal, ink, and pencil given practicality and access to materials. Viewers and visual translators of these captivating drawings and paintings are cautioned to critically consider the artist’s depictions, use of media, and specific subject matter, while carefully holding personal interpretations in mind. Art as documentation both portrays and records for future eyes the perils of these aspects of the constructed human condition beyond the frailty of words and language. In the moment of our gaze into captured time, we as viewers, and co-constructors of meaning, bear witness to the appalling conditions of tens of thousands of people imprisoned and denied their basic needs.

Landscapes

The comfort and solace of the beautiful landscapes portrayed by many artists re-envisioned the surrounding scenery beyond the imprisoning isolation of the camps. Starkly contrasting the openness, freedom, and sense of peacefulness beyond the perimeter of the camps, Karl Schwesig’s painting Mount Canigou in the Snow depicted the varying degrees of imprisonment of body, mind, and soul reflected in the mountains resolutely overlooking the St Cyprien camp and its barbed wire enclosures.

One particularly stunning piece, On the Way to the Ninth Fort for Extinction from the hand of Esther Lurie, portrays the road to death. Her idyllic image of the beautiful road marks in stark contrast, the path of murder and torture experienced by many hundreds of Jews, which included large numbers of young children in the Kovno ghetto. Here is her jarring description:

“A subject that I painted many times, in all seasons, was the road from the valley where the ghetto was up to the ‘Ninth Fort’ on the top of a hill. The tall trees lining the road gave it a special character. This road going up the hill is etched in my memory as the ‘road of torture’ along which thousands of Jews passed, Jews from Lithuania and from other parts of Western Europe, on their way to the death camps. There were days when the overcast sky created an atmosphere of darkness and tragedy, which well reflected our feelings.”

Portraits

Portraiture comprises a significant number of drawings and paintings surviving from the Holocaust period. One unique feature of Holocaust art is the historical documentation written on the respective portrait. This historical documentation includes the name of artist and the name of the subject and uniquely, also incorporates the specific day, month and year, the location, and occasionally a dedication. One example is this Portrait of Dr. Mautner by Malva Schaleck.

These artists created a path to witness for the viewer, reader, and interpreter—you. You (and I) are invited in/to the sacred space of lives silenced and given the opportunity to remember and bear witness. Each of us as readers and viewers face the opportunity to enter the intimate space of family captured in such historical albums.

References

- Karel Fleischman. A Day in Theresienstadt. Theresienstadt Archives, L303 401, 5. Translated from Czech by Rachel Har Zvi.

- Esther Lurie. Living Testimony—Ghetto Kovno. Dvir, Tel Aviv, 1958, 10

- Karel Fleischman. Erich Monck—A Shadow of a Man, Theresienstadt Archives, L303 401, 5. Translated from Czech by Rachel Har Zvi.

- Esther Lurie. “Notes of an Artist” from Notes for Holocaust Research, Second collection, February 1952, 113

- Karel Fleischman. Erich Monck—A Shadow of a Man, 1

ACTION 1

Think

What Have You Learned?

- Briefly write about the important functions Holocaust art performed during the period and contrast it with the role of art as documentation drawing on examples discussed.

- How might you consider the values imbedded in notions of beauty versus ugliness? What type(s) of tension are present in aesthetic values evoked through the artwork and the nature of the tragic depictions rendered?

- What are three of the different tensions arising in our consideration of subjectivity and objectivity? How are the tensions manifested in oppositional artistic (personal) expression and documentary (historical, factual) testimony?

- How would you engage the subject of the Holocaust artistically?

Further Reading

Janet Blatter, Sybil Milton, and Irving Howe, Art of the Holocaust, 1982

Every effort has been made to gain permission from copyright holders to reproduce borrowed material. The publishers apologize for any errors and will be pleased to rectify them in subsequent reprints and website programming

Educator Tools