Educator Tools

NEVER SHALL I FORGET that night, the first night in the camp, that turned my life into one long night seven times sealed.

– Elie Wiesel from Night

Published in English in 1960, Night is Elie Wiesel’s personal account of the Nazi death camps, and is one of the most significant testimonies of the Holocaust experience.

The artwork in the exhibit “After Night” was created by members of the Teaching to Learn Project. It was composed of thirty teachers and adolescents who brought multiple perspectives and horizons of experience to bear on their artistic interpretations, as they grappled with the difficult themes and unspeakable horrors documented in Wiesel’s Night.

Did you know about this?

Triangles

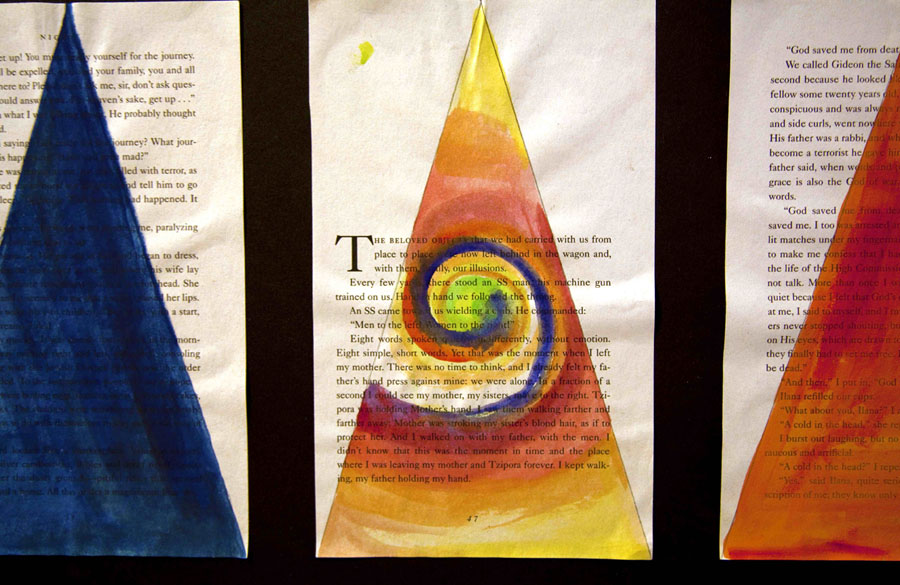

Nazis demarcated “undesirables” with badges made of triangles. Inverted triangles were an analogy for road hazard signs. Triangles of different colours were used to represent the different groups deemed as threats to the Nazi regime: red triangles designated political prisoners, especially communists; pink: sexual offenders and homosexual men; green: criminals; black: “asocials” and Roma (Gypsies); yellow triangles forming a Star of David, or two yellow triangles, combined, were used to mark Jews.

In the 1970s, gay rights advocates reclaimed the pink triangle as a form of protest and a symbol of pride. In the spirit of this activist reclamation, the artists painted triangles in colors chosen to represent diversity, solidarity, and individuality. This process included designing, cutting and painting on pages from Night. Colors for the large canvases were chosen and painted collectively. These paintings responded through color and symbol to themes in the Holocaust memoir by Elie Wiesel. Each painting contained nearly the entire text—96 of 113 pages— of Night. Their artistic interpretations of Night took place over the span of a year, and culminated in an art exhibit.

These people explored how Night could be a platform for literary and historical inquiry as well as a catalyst for social change. Wiesel (2005) himself noted that the purpose of Holocaust education is not to passively encounter the messages of survivors but rather to encourage readers themselves to become the messengers; or to paraphrase Paul Celan (2001), to act as “witnesses for the witnesses.”

This exhibition was a collective response to Wiesel’s testimony of his experiences in the Auschwitz and Buchenwald camps from 1944 until his liberation in 1945 at the age of 16.

One of the young artists shared her insights into the process and the symbolic and representational power of color in the After Night exhibit:

“After reading Night and completing the project, the colours used to paint the triangles are not just colours any more. The triangle that we painted blue was very interesting for me. It showed different levels in intensity in the colour (streaks) that could represent many things. It could mean the good and evil during the Holocaust. I saw it as [symbolizing] many different sides to the Holocaust. The different blotches of colour represent the different people involved, and how each person has their own story, whether they are a victim or an abuser.

Choosing the colours was more something I felt than thought of; I think for people viewing the exhibit it is the same. As there is no description of why we chose that colour or what we think it represents, it is really up to the viewers to determine what the colours mean and one way to do that would be to just feel.” As Robert Fulford said, “Trust the art, not the artist.” Like the artists themselves, middle school students who viewed After Night at the exhibit expressed a range of responses to the artwork, from the emotional and personal, to the aesthetic and historical.

Comments from Middle school observers:

“While I was walking through the exhibit, I was reminded of my great and great-great grandparents and how they died (in the concentration camps).”

“It was probably humiliating to wear a yellow or pink triangle but at the show it was turned into a symbol of pride. The multicolored triangles represented solidarity with the victims, and became more beautiful because [they] show colors together.”

“I liked this triangle both for its aesthetics (I loved its swirliness) and because to me, this symbolizes acceptance. In my perspective, the varied colors symbolized different types of people and the big purple swirl in the centre was a new type of people, easily blended with the others. “

“The many varieties of colored triangles created by the artists brings life and brightens and teaches a lesson to those who take the time to view [it]. He described feeling moved by “what the power of many can accomplish.”

ACTION 1

Think

A. What is the role of art after the Holocaust? Are films more or less effective than visual art?

B. How does this form of interpreting history affect viewers? Artists? Students?

C. Do these types of artwork memorialize or trivialize the pain and suffering of the Holocaust?

ACTION 2

Do

Designing a Two-Dimensional Memorial

- Use geometric shapes or forms to create a Holocaust memorial. Often we have emotional responses to certain shapes. For instance, if you compare several circles with a row of acute triangles, which seems more inviting? Which seems dangerous? You can also consider the position or orientation of shapes. For example, a triangle resting on its base is a very stable shape, but inverted it is unstable. A large shape leaning toward us can seem very threatening, but two shapes leaning against each other can be stable, suggesting support and even shelter.

- Use geometric shapes to create a Holocaust memorial to be constructed through geometry. What will be the purpose or theme of your memorial? Will it be dedicated to the memory of the victims or to one of the victim groups; will it commemorate the struggle, the agony, or the resistance of the victims; or will it acknowledge the heroism of rescuers and liberators?

- Use rulers, compasses, and a knowledge of geometry to draw and cut your shapes from a single colour of construction paper.

- After you have cut all the forms out, glue them together and arrange them on a second sheet of contrasting colour.

ACTION 3

Do

Designing a Three-Dimensional Model of a Memorial by Drawing, Painting or Creating a Model

Three options:

A. Create a modeled (shaded) drawing:

- Ensure there is a consistent light source and shade each of the forms to create the illusion of dimension.

- Or use a computer graphics program to create shaded forms.

B. Design a three-dimensional structure painted with a single colour to emphasize the forms:

- May be approached as an architectural memorial.

- View photographs of the architecture of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (use google images).

- Also consider the architectural memorials at Yad Vashem and visit the website of the South Florida Holocaust Memorial.

C. May be completed as an architectural rendering or as a model.

Every effort has been made to gain permission from copyright holders to reproduce borrowed material. The publishers apologize for any errors and will be pleased to rectify them in subsequent reprints and website programming

Educator Tools