Educator Tools

Ask yourself:

Ask yourself:

- How could millions of people be starved to death in 1932-1933 in the Soviet Union without international exposure?

- How could the conditions for a famine be created in a country known for its rich fertile soil and record-breaking harvests?

- What kind of psychological, social, and cultural scars does the trauma of prolonged hunger and starvation leave on its victims and their children?

Definitions

Definitions

Bolsheviks – the Russian word bolshevik means “one of the majority.” The bolsheviks were members of the majority faction of the Russian Social Democratic Party, which was renamed the Communist Party after seizing power in the October Revolution of 1917. They were leaders of the revolutionary working class of Russia and led by Lenin.

Collectivization – a Soviet government policy in which private ownership of farmland was discontinued. Land was forcibly taken from owners and amalgamated into government-owned structures known as collective farms, which were large agricultural units where people worked in a factory-like environment controlled by the totalitarian Soviet government.

Communism – a totalitarian system of government in which all the land, natural resources, industries, and institutions, including education and media are owned and controlled by the government. This system is based on political theory derived from Karl Marx who believed that capitalism would inevitably provoke revolutionary class warfare and result in the production of a society in which all property is publicly owned and each person works and is paid according to their abilities and needs.

Diaspora – a group of people who have been dispersed from the area in which they had lived for a long time or who are living outside the area in which their ancestors lived.

Gulag – a system of Soviet labour camps, including detention and transit camps and prisons, that existed from 1919 to the mid-1950s. By 1936, the Gulag held a total of 5,000,000 prisoners, a number that was probably equaled or exceeded every subsequent year until Stalin died in 1953. Besides rich or resistant peasants arrested during collectivization, people sent to the Gulag included purged Communist Party members and military officers, German and other Axis prisoners of war (during World War II), members of ethnic groups suspected of disloyalty, Soviet soldiers and other citizens who had been taken prisoner or used as slave labourers by the Germans during the war, suspected saboteurs and traitors, dissident intellectuals, ordinary criminals, and many utterly innocent people who were hapless victims of Stalin’s purges.

Halych-Volhynia State (also spelled Galicia-Volhynia) – a break-off principality formed in the western regions of the Kyivan Rus State during the late Middle Ages.

Kozaks (also spelled Cossacks) – Originally (in the fifteenth century) the term referred to semi-independent Tatar groups, which formed in the Dnieper region. The term was also applied (by the end of the fifteenth century) to peasants who had fled from serfdom in Poland, Lithuania, and Muscovy to the Dnieper and Don regions, where they established free self-governing military communities. In the 19th and 20th centuries, the Russians used Cossacks extensively in military actions and to suppress revolutionary activities. Under Soviet rule Cossack communities ceased to function as administrative units. In the 21st century, under Russian President Vladimir Putin, Cossacks resumed their historical relationship with Moscow.

Kulaks (Ukrainian term – kurkuli) – a wealthy or prosperous peasant, generally characterized as one who owned a relatively large farm and several head of cattle and horses and who was financially capable of employing hired labour and leasing land. Lenin’s introduction of the New Economic Policy in 1921 favoured the kulaks. Although the Soviet government considered the kulaks to be capitalists and, therefore, enemies of socialism, it adopted various incentives to encourage peasants to increase Soviet agricultural production and enrich themselves. In 1929, the government began a drive for rapid collectivization of agriculture. The kulaks vigorously opposed the efforts to force peasants to give up their small privately owned farms and join large cooperatives. At the end of 1929, a campaign to “liquidate the kulaks as a class” (dekulakization) was launched by the government. By 1934, when approximately 75 percent of the farms in the Soviet Union had been collectivized, most kulaks—as well as millions of other peasants who had opposed collectivization—were deported to remote regions of the Soviet Union or arrested and their land and property confiscated.

Kyivan Rus/Kievan Rus – the origin of the Kievan state and that of the name Rus, which came to be applied to it, remain matters of debate among historians. It was founded by the Viking Oleg, ruler of Novgorod from about 879. In 882, he seized Smolensk and Kiev, and the latter city, owing to its strategic location on the Dnieper River, became the capital of Kievan Rus. Extending his rule, Oleg united local Slavic and Finnish tribes, defeated the Khazars, and, in 911, arranged trade agreements with Constantinople. The thirteenth century Mongol conquest decisively ended Kiev’s power. Remnants of the Kievan state persisted in the western principalities of Galicia and Volhynia, but by the fourteenth century those territories had been absorbed by Poland and Lithuania, respectively. Russian, Ukraine, and Belarus all claim to be the modern successors of the medieval empire of Kievan Rus under Vladimir/Volodymyr the Great (c. 958 – 1015).

Industrialization – the transformation from a mainly agricultural society to one based on the manufacturing of goods and in which manual labour is replaced by mechanization.

Grand Duchy of Moscow/Muscovy – a medieval principality that, under the leadership of a branch of the Rurik dynasty, was transformed from a small settlement in the Rostov-Suzdal principality (that succeeded Kievan Rus) into the dominant political unit in northeastern Russia (Moscow).

Propaganda – used to manipulate other people’s beliefs, attitudes, or actions by means of symbols (words, gestures, banners, monuments, music, clothing, insignia, hairstyles, designs on coins and postage stamps, and so forth). Deliberateness and a relatively heavy emphasis on manipulation distinguish propaganda from casual conversation or the free and easy exchange of ideas. Propagandists have a specified goal or set of goals. To achieve these, they deliberately select facts, arguments, and displays of symbols and present them in ways they think will have the most effect. To maximize effect, they may omit or distort pertinent facts or simply lie, and they may try to divert the attention of people they are trying to sway from everything but their own propaganda.

Russification – laws, decrees, and aggressive actions taken by imperialist Russia and Soviet authorities aimed at imposing Russian language and culture, and social and political systems on all non-Russians.

Secret police – police established by governments to maintain social and political control. In Russia, the secret police suppressed political dissent through terror, intimidation, torture and killing. In the Russian empire, they were called by the acronym CHEKA, and later in the USSR, they were known as NKVD, OGPU, and KGB.

Totalitarianism – a form of government that permits no individual freedom and seeks to subordinate all aspects of individual life to the authority of the state. Any dissent is branded as evil, and internal political differences are not permitted. Nazi Germany (1933–1945) and the Soviet Union during the Stalin era (1928–1953) were the first examples of decentralized or popular totalitarianism, in which the state achieved overwhelming popular support for its leadership. That support was not spontaneous; its genesis depended on a charismatic leader, and it was made possible only by modern developments in communication and transportation.

Ukraine in Europe

Credit: Wikipedia

This really happened

The Famine of 1932-1933 is called the Holodomor, a Ukrainian word that means murder by starvation. The Holodomor is known as a man-made famine because it was not caused by crop failure or natural disaster. Joseph Stalin created the conditions for mass starvation in order to destroy the people who dared to oppose his government’s plan for collectivization and industrialization.

Earlier historians of the Soviet Union presented various explanations for the Famine of 1932-1933, such as excesses in the Soviet drive for collectivization, the slaughter of livestock by farmers opposed to collective farms, drought, and a poor harvest. However, most scholars today recognize that the Famine was deliberately planned and engineered and was not the result of natural causes, such as drought or a poor harvest. During the years of the Famine, the weather conditions were favourable and the harvest was plentiful enough to feed the entire population of Ukraine, as evidenced by official government reports from those years. Survivor accounts confirm that the Famine was artificially created by Stalin’s government. The government imposed crop quotas that were excessive, demanding that the entire harvest in the fields of Ukraine be confiscated, as well as all food supplies in people’s homes.

By the fall of 1932, the rural population of Ukraine was starving. Laws, such as the Decree of August 7, 1932, made it a punishable crime to gather and hide for oneself any produce from the fields, as these were declared to be “socialist property.” Entire regions of Ukraine were placed under food blockades, with orders to halt the delivery of food to stores in these regions. Distressingly, as millions lay dying in the streets and in village huts, Soviet granaries were filled to capacity with the year’s harvest. Large shipments of Soviet grain were sold to Germany and other countries, contributing to a depression-era drop in the price of wheat in Europe.

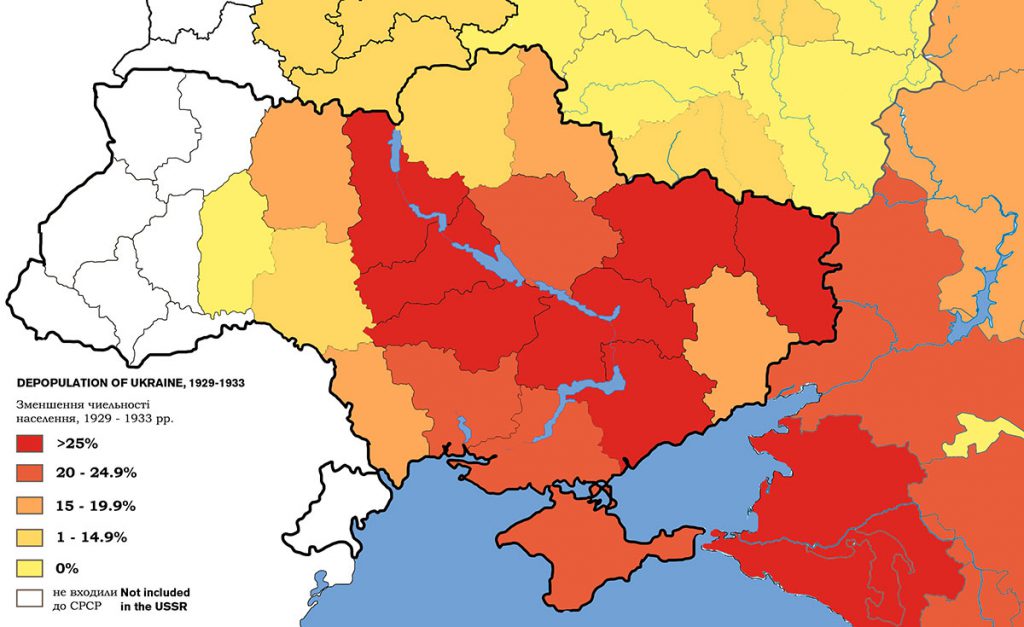

Soviet regions just outside the borders of Ukraine experienced minimal food shortages. Police patrols had to be placed on Ukraine’s borders during the time of the Holodomor to keep starving Ukrainians from crossing into Russia where they could obtain food to survive.

Official documents and materials now available to the public confirm the extreme lengths taken by Stalin’s regime to suppress news of the Famine in 1932-1933. Soviet authorities ordered the press to deny the existence of the Famine, and punished anyone who spoke or wrote about it. The country was eventually closed to foreign correspondents. The suppression of the truth continued for several decades until the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

The few western journalists who travelled to Soviet Ukraine in 1932-1933 were too intimidated to write about what they were witnessing at the time. They chose to share their experiences after they were safely at home. Journalists such as Malcolm Muggeridge and Gareth Jones were appalled by the starvation and loss of life, particularly in central Ukraine. Unfortunately, one very influential journalist, Walter Duranty, denied that he had witnessed the horrible results of the Famine in exchange for lavish Soviet favours. Duranty’s articles for The New York Times in 1932-1933 convinced many people that reports of starvation in Ukraine were untrue. He pointed to large grain exports from the Soviet Union as proof that all was well in Ukraine.

Since the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, researchers have gained access to government documents and Communist Party archives. They have found numerous documents that prove the conditions for forced famine were created by Stalin’s regime. Stalin himself admitted to Prime Minister Winston Churchill that 10 million peasants died in Ukraine and neighbouring regions in the 1932-1933 Famine. He viewed this as successful revenge against people who were considered to be hostile to the Soviet communist system.

Adapted from the Genocide Never Again Workbook. Used with permission.

While the exact number of victims is impossible to assess in any case of genocide, scholars today put the number of victims in Ukraine at 3.9 million.

Read historian Anne Applebaum on how Stalin hid the famine from the world. Her book Red Famine: Stalin’s War on Ukraine (2017) is an award-winning history of the genocide. Listen to her discuss the book.

Map of depopulation of Ukraine and southern Russia, 1929-1933. Territories in white were not part of the USSR during the famine.

Credit: Wikipedia

Historical Context

Ukrainians trace their historical roots to the Kyivan Rus state and an East Slavic tribe, the Polianians. The thirteenth century Mongol conquest decisively ended Kiev’s power. Remnants of the Kievan state persisted in the western principalities of Galicia and Volhynia, but by the fourteenth century those territories had been absorbed by Poland and Lithuania, respectively.

The town of Moscow was founded in 1147. Moscow’s authority was greatly enhanced when in 1326 the metropolitan of the Russian Orthodox Church transferred his seat from Vladimir to Moscow. Thereafter the town was to remain the centre of Russian Orthodoxy, and after the fall of Constantinople to the Turks in 1453 it claimed the title of the Third Rome. Muscovy was the foundation for the future Russian empire.

In the nineteenth century, Russian leaders introduced the secret police and continued imperial expansion, making russification of all ethnic groups a government policy. It was at this time that some of the descendants of the Kyivan Rus state began to refer to themselves as Ukrainians, in order to clearly differentiate their nationality from Muscovites/Russians.

Following the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II of Russia in 1917, the bolsheviks under the leadership Vladimir Lenin seized power. Lenin believed that a transition to communism required a period of dictatorship. The bolsheviks laid claim to all lands of the former Russian empire. They established their own secret police to imprison and execute anyone who opposed Soviet dictatorship, calling them “enemies of the state.”

In 1917, Ukrainians declared independence and created the Ukrainian National Republic, but were soon overrun by German and Austrian forces. A civil war ensued on Russian-held territory as the bolsheviks continued to consolidate power. Six different armies were operating on Ukrainian lands during this time of anarchy and collapse of authority. When Ukraine was allied with Poland for a short term it gained some ground, but by 1920 all of eastern and central Ukraine except Crimea was taken over again by the bolsheviks. In 1922, the communists created the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (U.S.S.R.) as a federation of Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, and Transcaucasia. When the U.S.S.R. collapsed in 1991, Ukraine became an independent state.

Timeline

The following timeline provides an overview of historical events leading up to the Holodomor. It traces Ukraine’s history from 1918 to the present day.

| UKRAINIAN SOVIET SOCIALIST REPUBLIC | Year | RUSSIAN EMPIRE |

|---|---|---|

| Ukrainian National Republic | 1917 | Bolsheviks create the Russian Soviet Federated Socialist Republic. |

| Ukraine declares a short-lived United Ukrainian National Republic by incorporating Western Ukrainian lands | 1919 | |

| Ukrainian nationalist forces unable to repel foreign aggression (Red Army, White Army, Poles, Entente); leaders forced into exile. | 1918 – 1921 | War; communism; bolshevik policy aims to establish a totalitarian socialist order; nationalizes all productive property; Cheka (secret police) and the bolshevik Red Army suppress worker and peasant uprisings. |

| Ukrainian lands divided up between four countries: Russia, Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Romania. | 1921 | Red Army takes most of Ukrainian territory. A period of inflation, food rationing, forced labour and economic collapse ensues. |

| First Famine in Ukraine The expropriation of grain, a poor crop and severe food rationing during the civil war results in 1.5-2.0 million deaths by starvation in Ukraine. | 1921 – 1923 | The expropriated food is sent to feed Russian cities and the Red Army. |

Source: O. Subtelny, 2009. Ukraine: A History, Fourth ed. Toronto, 380-381.

| UKRAINIAN SOVIET SOCIALIST REPUBLIC | Year | RUSSIAN SOVIET FEDERATED SOCIALIST REPUBLIC |

|---|---|---|

| 1922 | Russia creates the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), including Russia, Ukraine, Belarus and Transcaucasia. Ultimate control, however, is in the hands of the Central Committee of the Communist Party in Moscow. | |

| In Ukraine, this policy is called ‘Ukrainization’ and results in a significant social, political, cultural renaissance, as well as the spread of a national consciousness. Source: P. Magocsi, 1996. A History of Ukraine, Toronto, 533-547 | 1923 | The USSR introduces a policy to recruit non-Russians into the Communist Party. |

| 1924 | Vladimir Lenin dies and a struggle for power sees Joseph Stalin take control of the Communist Party. Stalin aims to make all non-Russian republics into one single Russian communist state. He uses the OGPU, successor to Cheka secret police, to eliminate all internal opposition. Through terror, deportations, and executions, Stalin assumes complete control. | |

| Of the approximate 29 million people in Ukraine, 80% are ethnic Ukrainians and 89% of the farming sector is Ukrainian and demonstrates little desire for communist totalitarianism. | 1926 | Stalin fears that the peasant class, which owns agricultural land, is the social base of Ukrainian nationalism, and are thus, “enemies of the state.” |

| Collectivization meets with opposition from successful, wealthier, independent farmers. | 1928 | Stalin introduces the first Five Year Plan, a state imposed revolution from above, focused on rapid industrialization to modernize the USSR. He initiates forced total collectivization of agriculture (from private farms into state-owned) so the state can sell grain abroad and pay for industrialization. |

Stalin directs his secret police, the OGPU, to arrest Ukrainian political, intellectual, and religious leaders for allegedly belonging to a fictitious Union for the Liberation of Ukraine and conspiring for the separation of Ukraine from the USSR. Next, he liquidates the Ukrainian Autocephalous (autonomous) Orthodox Church, and sends bishops and priests to labour camps. Through executions, deportations or exile to the Gulag (Soviet prison camps), over 600,000 farmers and their families are liquidated, their property transferred to collective farms. Moscow sends in urban workers to expropriate property, organize collectives and supervise grain shipments; peasant uprisings are quelled by the regular army and OGPU units; any protesters are imprisoned or killed. Peasants slaughter farm animals in protest. | 1929 – 1931 | Stalin regards Ukrainian nationalist tendencies as an impediment to building socialism. The Soviet state labels successful farmers as kulaks and “enemies of the state” and Stalin calls for the “liquidation of the kulaks as a class.” Stalin launches an attack on the remaining mass of farmers, most of whom oppose collectivization. |

Famine spreads in Ukraine. There is not enough grain to meet government demands and to feed people. Many peasants flee collective farms, and seek food in towns and cities. The Ukrainian Communist Party pleads with Stalin to lower grain quotas. Famine (Holodomor) rages in Ukraine Swollen from hunger, desperate peasants eat rats, tree bark, and leaves to try to survive. Numerous cases of cannibalism are recorded. Demographers claim that at least four million men, women, children have starved to death in Ukraine as well as at least 600,000 deaths in the predominantly Ukrainian Kuban region. | 1932 | The state creates penalties and policies making private farming economically impossible, sets unrealistically high grain quotas for collective farms, and demands they give up seed grain reserves. > August: Red Army units, OGPU secret police, and urban Russian communist activists act as enforcers. > November: > December |

In a meeting with Winston Churchill in 1942, Stalin admits to 10 million deaths during collectivization. During the spring and summer of June – July 1933:

Western governments, such as Great Britain, France, USA and Canada, are aware of the Holodomor but choose not to interfere in the “internal affairs of the USSR.” The Holodomor Legacy The famine provides a path to Soviet repopulation of areas where massive starvation occurred. Through the addition of Russian and other Soviet peoples into Ukraine and the dispersion of Ukrainians throughout the Soviet Union over several years, ethnic unity is destroyed and nationalities are mixed. | 1933. | > January Stalin appoints Postyshev to speed up grain collection and to reprimand Ukrainian communists for failing to meet quotas. Some communists begin calling Stalin’s brutality in Ukraine genocidal. Postyshev’s gangs of activists conduct brutal house searches, tear up floors and walls looking for grain. Watchtowers are placed around farm fields; guards are directed to shoot anyone picking crops for food. At the height of this artificially-induced Famine (Holodomor), Stalin’s unrelenting drive to finance industrialization sees the Soviet government selling wheat to other countries at below-market prices. The Soviet government denies the Famine, and refuses help from international charitable organizations like the Red Cross. (Soviet propaganda and disinformation campaigns continue this denial into the 1980s) |

Ukrainian communist officials are replaced by Russian officials. Ukrainian cultural and political leaders are imprisoned or killed. Any spoken or written mention of the Holodomor is strictly forbidden and harshly punished. By Soviet policy, Russian is to become the language and culture of all of the peoples of the USSR. | 1933 – 1938 | The Great Terror: |

The Ukrainian Communist Party declares the Famine was a “national tragedy,” but does not admit that is was genocide. | 1990 |

|

Ukraine declares its independence after the USSR dissolves. | 1991 |

|

| President Viktor Yushchenko, Ukraine’s first pro-Western leader, and the Ukrainian parliament recognize the Holodomor as a genocide. | 2006 | Russian parliament passes a resolution denying that the Holodomor was a genocide. |

| Pro-Russian Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych rejects the Holodomor as a genocide. | 2010 | |

| Euromaidan (Revolution of Dignity) Massive public protests by Ukrainians, similar to those that took place on the Maidan in 2004, demand integration into Europe after President Yanukovych refuses to sign an association agreement with the European Union. Millions of people gather in Independence Square in Kyiv to protest corruption and human rights violations and eventually force President Yanukovych to flee the country. | 2014 | Fearing a resurgence in Ukrainian nationalism, Russia annexes the Crimea and begins using hybrid warfare to destabilize Ukrainian sovereignty. |

| The Holodomor is presented as a genocide in history texts and is studied by students in Ukrainian schools. | 2015 | The Kremlin continues to deny the Holodomor. |

Sources

Magocsi, P. 1996. A History of Ukraine, Toronto.

Klid, D. & Motyl, A. 2012. The Holodomor Reader, Toronto.

Hrushevsky, M., 1970. A History of Ukraine, Yale.

Hrushevsky, M., 1999. History of Ukraine-Rus’, Vol. 7, Edmonton, Toronto.

Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine. Kyivan Rus

Kuryliw, V., 2016. Holodomor in Ukraine

The timeline traces Russian imperialist aggression toward Ukraine beginning in the nineteenth century. You will notice that the Holodomor was one in a series of attempts by Russian imperialists and later Soviet authorities to dominate the land and people of Ukraine. However, the Holodomor was the most ruthless of all in that Stalin’s decrees created the conditions for genocide. As reports of starvation continued to surface, there was no compassion and no reversal of the plan. Stalin was determined to destroy Ukrainian citizens who openly defied communist ideology and collectivization within the USSR. The result was massive starvation of millions of men, women, children, and infants.

This engineered famine and tragic loss of millions of lives has slowly gained international recognition–Canada was the first western country to acknowledge the genocide. However, there are still many countries that do not officially recognize the events of 1932-1933 as a genocide created by the totalitarian regime of Joseph Stalin. Let’s take some time to examine primary and secondary sources of information.

Listen to an eyewitness account

Dying peasants on the streets of Kharkiv during the Famine-Genocide (1933 photo by A. Wienerberger)

Source: www.encyclopediaofukraine.com/

Artifact 1: Politburo Resolution on Grain Procurement in Ukraine

Artifact 1: Politburo Resolution on Grain Procurement in Ukraine

No.44 Resolution of the CC AUCP(b) Politburo on grain procurement in Ukraine

January 1, 1933

The CC CP(b)U and Ukrainian SSR RNK shall widely inform village councils, kolhosps, collective farmers and proletarian private farmers that:

Secretary, CC AUCP(b), J. Stalin

a) Those who hand in any grain that was previously misappropriated or concealed will not be subject to repressions;

b) Those collective farms, collective farmers and private farmers who stubbornly insist on misappropriating and concealing grain will be subject to the strictest punitive measures provided by the USSR Central Executuve Committee Resolution of August 7, 1932 “On the safekeeping of property of state enterprises, collective farms and cooperatives and strengthening public (socialist) property.”

RGASPI, fond 17, list 3, file 913, sheet 11.

CC AUCP (b) – Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolshevik) based in Moscow

CC CP (b) U – Central Committee of the Communist Party (Bolshevik) of Ukraine based in Kharkiv

RGASPI – Russian State Archive of Socio-Political History

Ukrainian SSR RNK – Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic Rada Narodnykh Komisariv (RNK), or Council of Peoples’ Commissars of the Ukrainian Socialist Soviet Republic

Source: Holodomor of 1932-33 in Ukraine: Documents and materials. Compiled by Ruslan Pyrih. Kyiv Mohyla Academy Publishing (2008), 77.

Artifact 2: Report from the Consul of Italy in Kharkiv

Artifact 2: Report from the Consul of Italy in Kharkiv

No. 67 Report from the Consul of Italy in Kharkiv to the Minister of Foreign Affairs of Italy on “Famine and Sanitary Conditions” (excerpt)

July 10, 1933

The current situation in Ukraine is horrific. Apart from larger towns and raions within a fifty kilometer radius of cities, the country is engulfed in famine, typhus and dysentery. There are also cases of cholera and even plague which until recently were sporadic. […]

The famine has decimated half the rural population.

Police apprehend fleeing peasants with livid brutality (I have noticed that the urban population willingly takes part in this hunt for villagers, either because of some incomprehensible feeling of self-defence, or under the influence of crafty propaganda, or an overwhelming desire to commit torture). If somebody tries to escape from the police transports, there are always a dozen city residents prepared to chase him down, beat him up and turn him over to the police. There are orders prohibiting doctors from administering medical treatment to villagers in the cities.

Two thousand such poor souls are rounded up every day and shipped out during the night. Entire families, that came to the city in the last hope of avoiding death from starvation, are held in barracks for one or two days and then transported, hungry, 50 kilometers from Kharkiv and thrown into rain-formed gullies.

Many of them that can no longer move and simply die on the spot; some manage to escape and others are fortunate enough to make it back to the city where they end up begging for food. One of them told me about an area located between the ponds beyond Rai-Yelenivka, a four-hour walk away from nearest railway station. Every three to four days, a team of gravediggers is dispatched there to bury the dead.

Some doctors whom I know confirmed that death rates in the villages often reach 80 percent, but never less than 50 percent. Kyiv, Poltava and Sumy oblasts were most afflicted by the famine and can be described as depopulated.

I am adding another name to the list of dead villages: Lutova near Kharkiv. Prior to the famine its population was 1,500. Today it is just under 90.

As for sanitary conditions, they can be no worse than their current state. Doctors are prohibited from speaking about typhus and death from starvation. They are also prohibited from compiling statistics that may be interesting from the scientific point of view. Nonetheless, I was able to obtain the following information about pathologies due to undernourishment. People who are unable to secure bread (very black bread with various additives) gradually grow weaker and die of heart failure without any signs of disease. Meanwhile, those who consume only fluids and milk experience swelling of their joints and legs. They also die from heart failure.

Source: Holodomor of 1932-33 in Ukraine: Documents and materials. Compiled by Ruslan Pyrih. Kyiv Mohyla Academy Publishing (2008), 114-115.

Artifact 3 – Population Figures

Artifact 3 – Population Figures

Population Figures for the East Slavic Nationalities and the USSR as a Whole

| Taken from: The Great Famine in Ukraine: The Unknown Holocaust. Published by the Ukrainian National Association, p. 33. The source of information is “Natsionalisti SSR” by Kozlov, p. 29. Small Soviet Encyclopedia, 1940 edition, under “U” – “Ukrainian SSR”; Ukraine’s population in 1927 census listed at 32 million; in 1939 (twelve years later) – 28 million. | ||||||

| 1926 | 1939 | % Change | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | % | Population | % | |||

| USSR | 137,397,000 | 100.0 | 170,557,100 | 100.0 | +16.0 | |

| Russians | 77,791,001 | 54.0 | 99,591,500 | 54.0 | +28.0 | |

| Byelorussians | 4,738,900 | 3.3 | 5,275,400 | 3.1 | +11.3 | |

| Ukrainians | 31,195,000 | 21.6 | 28,111,000 | 16.5 | -9.9 | |

Number of Children Attending Schools

| Source: Cultural Construction of the USSR, Moscow: Government Planning Pub., 1940, pages 40-50. Charts reprinted from the Genocide Never Again Workbook. Used with permission. | |||

| Dates | Russian SFSR | Ukraine | Byelorussia |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1914-1915 | 4,965,318 | 1,492,878 | 235,065 |

| 1928-1929 | 5,997,980 | 1,585,814 | 369,684 |

| 1938-1939 | 7,663,669 | 985,598 | 358,507 |

Artifact 4 – Resettlement Directives

Artifact 4 – Resettlement Directives

No. 68 Resolution of the USSR SNK on resettlement to Kuban, Terek and Ukraine

August 31, 1933

Chairman, USSR Council of Peoples’ Commissars,

The Council of People’s Commissars of the Union of SSR resolves:

The All-Union Resettlement Committee of the Council of Peoples’ Commissars of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics shall organize the resettlement of 10,000 families to Kuban and Terek, and 15,000-20,000 families to Ukraine (Steppe) by the beginning of 1934.

V. Molotov (Skryabin)

Executive Director, USSR Council of Peoples’ Commissars,

I. Miroshnikov

No. 69 Resolution of the CC CP(b)U Politboro on additional resettlement of Steppe raions (excerpt)

September 11, 1933

Prepare the following numbers of additional resettlements to the Steppe raions during the fourth quarter of 1933: 22,000 families to Dnipropetrovsk, 9,000 families to Odesa and 4,000 families to Donetsk oblasts.

Recruit additional resettlers from among those collective farmers, laborers and private farmers who are willing to join the collective farms of the Steppe.

Establish the following recruitment targets: 8,000 families each from Kyiv and Chernihiv oblasts and 6,000 families from Vinnytsia oblast.

Conduct additional resettlement to Dnipropetrovsk oblast from Kyiv and Chernihiv oblasts, to Odesa oblast from Vinnytsia and Kyiv oblasts, and to Donetsk from Chernihiv oblast. […]

SNK – Council of People’s Commissars of the USSR (Soviet Narodnyhkh Komisariv)

CC CP (b) U – Central Committee of the Communist Party (Bolshevik) of Ukraine based in Kharkiv

Source: Holodomor of 1932-33 in Ukraine: Documents and materials. Compiled by Ruslan Pyrih. Kyiv Mohyla Academy Publishing (2008), 116-117.

Artifact 5: International Recognition of Holodomor

Artifact 5: International Recognition of Holodomor

Canada recognizes the Holodomor as an act of genocide against the Ukrainian people. In addition to Canada, other countries who recognize the Holodomor are:

- Argentina

- Australia

- Colombia

- Czech Republic

- Estonia

- Ecuador

- Georgia

- Hungary

- Latvia

- Lithuania

- Mexico

- Paraguay

- Peru

- Poland

- Portugal

- Slovak Republic

- Ukraine

- USA

- Vatican

Canada Remembers Holodomor Victims

In 2003, the United Nations (UN) and delegations from 25 countries issued a Joint Statement on the Great Famine of 1932-1933 in Ukraine (Holodomor). The opening statement reads as follows:

In the former Soviet Union millions of men, women and children fell victims to the cruel actions and policies of the totalitarian regime. The Great Famine of 1932-1933 in Ukraine (Holodomor), which took from 7 million to 10 million innocent lives, became a national tragedy for the Ukrainian people. [Correction: today, the scholarly consensus put the number of victims at 3.9 million.]

While the UN considers the Holodomor a national tragedy, they fall short of using the term genocide. In 1990, the UN International Commission of Inquiry into the 1932-1933 Famine in Ukraine (Geneva) concluded that the Famine in Ukraine was in fact a genocide. At the same time, the Commission could not confirm that the Moscow authorities had a preconceived plan to organize a famine in Ukraine. The only dissenting opinion came from Professor Sundberg, the head of the commission, who concluded that: “the evidence shows that the famine situation was well-known in Moscow from the bottom to the top. Very little or nothing was done to provide some relief to the starving masses. On the contrary, a great deal was done to deny the famine, to make it invisible to visitors, and to prevent relief being brought.”

Artifact 6 – An Author’s Chronicle of Events

Artifact 6 – An Author’s Chronicle of Events

Following an unofficial trip to Ukraine in 1933, journalist Gareth Jones shared his stories of government oppression and famine with George Orwell, a young British author. Years later, Orwell wrote the novel Animal Farm in which he satirized the corrosive effects of communism. He also alluded to an artificial famine and the need to conceal it from the outside world in chapter seven of his novel.

“For days at a time the animals had nothing to eat but chaff and mangels. Starvation seemed to stare them in the face. It was vitally necessary to conceal this fact from the outside world. Emboldened by the collapse of the windmill, the human beings were inventing fresh lies about Animal Farm. Once again it was being put about that all the animals were dying of famine and disease, and that they were continually fighting among themselves and had resorted to cannibalism and infanticide. Napoleon was well aware of the bad results that might follow if the real facts of the food situation were known, and he decided to make use of Mr. Whymper to spread a contrary impression.”

Orwell created a different preface to his novel in an underground Ukrainian edition of Animal Farm that was published in 1947. The translated edition was circulated throughout displaced persons’ camps in Europe following World War II.

Artifact 7 – Intergenerational Impact of the Holodomor

Artifact 7 – Intergenerational Impact of the Holodomor

Researchers have found that collective trauma is passed down from generation to generation, a phenomenon known as intergenerational trauma. In Canada, the impact of intergenerational trauma has been highlighted by survivors of residential schools. It is what happens “when untreated trauma-related stress experienced by survivors is passed on to second and subsequent generations. The trauma inflicted by residential schools and the Sixties Scoop was significant, and the scope of the damage these events wrought wouldn’t be truly understood until years later.”

A research study by Brent Bezo and Stefania Maggi (The Intergenerational Impact of the Holodomor Genocide on Gender Roles, Expectations, and Performance: The Ukrainian Experience, 2015) investigated how three consecutive generations perceived the impact of the Holodomor on their lives in modern-day Ukraine. The findings indicate that:

“intergenerational trauma, stemming from the Holodomor genocide, continues to exert its effect through gender-specific impacts. These impacts seem to occur at the individual level, in terms of affecting well-being and behaviours. The participant reports also suggest that collective trauma has a long-term, intergenerational impact on how men and women view themselves and each other, in a broader sense and in relation to gender roles, expectations, and performance. In this respect, participants did not only refer to themselves or known individuals in their own personal environments, but also spoke about a wider impact affecting the greater Ukrainian context. As such, our results suggest that the Holodomor had an impact at the societal level. This result reflects an area that has not been extensively studied and has yet to be well understood, but is consistent with the view that collective traumas play a critical role in shaping socio-cultural norms and values beyond the individual level. The impact of genocides at the societal level has implications for how interventions may address the healing of collective trauma and its intergenerational transmission, which may require the application of multi-level frameworks. Specifically, our results suggest that the healing of collective trauma also requires an understanding of gender-related impacts, in that victimization of men via gendercide might also result in a hidden or less overt intergenerational victimization of women. Hence, the historical roots of collective trauma should be considered for healing its intergenerational impacts.” (3-4)

The Press – Facts versus Fake News

Previously sealed files from the Soviet era are now available to historians and researchers. Many of the documents from the files provide compelling evidence of a government-imposed famine, with losses of 3.9 million people in the Ukrainian lands and 1.1 million in the grain-growing regions of Soviet Russia and Kazakhstan.

Unfortunately, in 1932-1933 evidence of the famine was kept well-hidden. Journalists were rarely allowed into Ukraine due to a travel ban. At least three noteworthy journalists did manage to travel to the region, one with the permission of Soviet authorities, and two who ignored the travel ban. The articles they wrote convey divergent views.

Read the article written by Ian Hunter titled “A Tale of Truth and Two Journalists.” Study the summary of interpretations offered in the chart and examine the articles published by both Malcolm Muggeridge and Walter Duranty (links given) to gain greater insight into each interpretation.

Note: Duranty’s article was written in response to the eyewitness accounts of journalist Gareth Jones. Walter Duranty travelled with the permission of Soviet authorities. Malcolm Muggeridge and Gareth Jones ignored the travel ban and went on their own.

| Genocide Believer: Malcolm Muggeridge | Genocide Denier: Walter Duranty |

|---|---|

|

|

The University of Alberta’s Holodomor Research and Education Consortium offers some reasons for the lack of awareness by the public about the artificial Famine of 1932-1933. It is interesting to note that even though many detailed accounts of the Holodomor were written, Duranty’s articles, which were backed by Soviet authorities, overshadowed the work of other journalists.

ACTION 1

Discuss

- Why was the Holodomor denied for so long and what ended the controversy?

- Can historical facts be denied when there is archival proof? Consider other examples of genocide denial such as Holocaust denial and denial of the Armenian genocide.

Write your answers and then discuss as a class.

ACTION 2

Do

Why is it that the earliest accounts of the Holodomor originated from diaspora Ukrainians and not from survivors living within Ukraine?

Write your answer and then discuss and compare with a partner in class.

ACTION 3

Do

Although the Holodomor of 1932-1933 is now widely recognized (see Artifact 5), Canada prides itself on being the first country in the world to declare that the Soviet engineered famine was a genocide against the Ukrainian people.

The Senate calls upon the Government of Canada “to recognize the Ukrainian Famine/Genocide of 1932-1933 and to condemn any attempt to deny or distort this historical truth as being anything less than genocide.” June 17, 2003.

In 2008, a private members’ bill was introduced to establish a day of remembrance for the Holodomor, Ukrainian Famine and Genocide (“Holodomor”) Memorial Day.

- Read about the introduction of Bill C-459. Which speaker, in your view, had the most compelling presentation?

- Select and record six pieces of information about the Holodomor that were shared by the speakers and captured your attention.

- Discuss as a class: Why is it important to recognize the Holodomor as a genocide?

- Are there other examples of historic injustices recognized by Canada’s parliament? Work in pairs to research and record your answers.

ACTION 4

Discuss

After viewing Artifacts 1, 2, and 3, reflect on the following questions:

- Statistical data and documents from the years 1932-1933 were released to the public following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. Given these new sources of evidence, do you think that the integrity of journalists such as Malcolm Muggeridge and Gareth Jones will be restored? Explain your reasoning.

- Create a five-minute presentation to the Pulitzer Prize committee about Walter Duranty’s award, and present it to your class.

ACTION 5

Think

A. Holodomor survivors who escaped to countries such as Canada have shared eyewitness accounts of cruelty and starvation in Ukraine during 1932-1933.

- There was no mention of the artificial famine, the Holodomor, in school textbooks in the Soviet Union, including Ukraine. Reflect on why this information was left out of the school curriculum.

- Germany has set an example by recognizing the crimes of Nazi Germany and trying to come to terms with this history. Reflect on the political, cultural, educational, economic, and geographic implications for Russia if government authorities were to accept responsibility for the Holodomor.

B. The next question refers to George Orwell’s Animal Farm. If you have read it, please proceed.

Andrea Chalupa has researched Orwell’s introduction to the Ukrainian version of Animal Farm (see Artifact 6). She speaks of the “revived revolutionary spirit” among displaced persons (DPs) upon reading this satire about communism, collective farms, and famine. Do you think that Orwell’s book motivated Ukrainian survivors to share their recollections of the Holodomor in the diaspora? Why or why not?

ACTION 6

Do

Artifact 7 explores intergenerational trauma. Define the following terms related to the history of residential schools in Canada: colonization, mistrust, indigenous inhabitants, cultural genocide, intergenerational trauma, and resettlement.

- Using your definitions, work with a partner to draw parallels and contrasts between residential schools and the Holodomor.

- Is it ever acceptable to compromise human rights to build a nation? Reflect on this topic and record your answers. Make a presentation to classmates, with a clear explanation of your views.

The Holodomor and the Great Leap Forward in China

Twenty-five years after Stalin’s Holodomor, General Mao Zedong launched the “Great Leap Forward” in 1958. Both communist leaders wielded apparently unlimited power in their efforts to eliminate private farms and promote rapid industrialization. According to an expert on the subject, historian Frank Dikötter, Mao’s policies precipitated mass famine, rampant cannibalism, causing an estimated 30 million deaths.

Dikötter, Frank – Mao’s Great Leap to Famine. International Herald Tribune. December 15, 2010

ACTION 7

Do

A. Select 10 adult participants for a history survey. First thank them for participating and let them know they will be identified only by number with no names recorded.

B. Question for them:

What do you know about the Holodomor and the Great Leap Forward?

C. Give them scores out of a total of 5 based on correct answers to:

Where? When? What? Who? Why?

- (Where) know that Holodomor refers to the Ukrainian genocide and the Great Leap Forward was a Chinese genocide.

- (When) provide dates (1932-1933 Holodomor; 1958-1962 GLF) or in the correct decade.

- (What) express a rough approximation of the number of man-made deaths attributed to the Holodomor (3.9 million) and the Great Leap Forward (30 million).

- (Who) know that General Mao was behind the GLF and Stalin was behind Holodomor.

- (Why) know that both famine-genocides were created by communists who wanted to eliminate private farms and rapidly increase industrialization.

D. Participants may be asked to volunteer their level of education and how they learned about these genocides.

E. Analyze your results as individuals and then as a class looking at trends and the potential explanations of those trends.

Every effort has been made to gain permission from copyright holders to reproduce borrowed material. The publishers apologize for any errors and will be pleased to rectify them in subsequent reprints and website programming

Educator Tools